Key Takeaways:

- Inflammaging is age-related inflammation. A healthy inflammatory state is associated with a healthy aging process.

- Senescent cells, which secrete pro-inflammatory molecules, accumulate with age and contribute to inflammaging.

- Aging immune cells, not only fail to clear senescent cells, they become senescent themselves, secreting their own inflammatory molecules and creating a snowball effect.

- Compounds that target inflammaging markers and senescent cells can help support a healthy inflammatory response.

Related Products:

Format: An advanced immune supplement combining Elysium’s Inflammaging Complex (a patented blend of tamarind and turmeric extracts, clinically proven to promote a healthy inflammatory status) with Elysium's Senolytic Complex (a senolytic formulation proven to clear senescent cells in two different human cell lines in laboratory studies).

Senolytic Complex: Whether your goal is managing inflammaging, healthy aging, or supporting an active lifestyle, you can easily personalize your senolytic protocols with three different dosing options.

Inflammation gets a lot of bad press these days; it’s blamed for everything from acne to achy joints. But did you know that short-term inflammation (also known as acute inflammation) is actually a good thing? An inflammatory response occurs when your immune system senses unwelcome visitors, such as germs, or perceives threats due to infection or injury. The inflammatory process is how your body protects itself and jumpstarts the healing process.

For example, exercise causes a short-term inflammatory response during which, the body increases blood flow to the affected area to deliver oxygen and nutrients, and remove waste. This is part of the body’s natural healing process when we work out.

Yet sometimes, inflammation happens for other reasons—when your body doesn’t necessarily need to be in fight mode. For example, during the aging process—a phenomenon known as inflammaging or age-related inflammation. It’s somewhat of a vicious cycle, too: The aging process increases inflammation, and age-related inflammation can make you more prone to age-related conditions.

The term “inflammaging” may sound like a buzzy social media word, but it’s actually a scientific term used to describe this type of age-related inflammation, and there is a ton of clinical research published on the topic.

Another cellular process that occurs with age is senescence. Senescence is a phenomenon that occurs when cells stop replicating and dividing, but they don’t die off as they should once they’re too old or too impaired to replicate again. The issue with these senescent cells is that they excrete pro-inflammatory factors that can impact neighboring and distant healthy cells and tissue. While your body does clear senescent cells, it’s less efficient at doing so over time, and senescent cells accumulate with age.

So, is there a relationship between inflammaging and senescence? Research suggests there is. Here’s what you need to know about aging, inflammation, and senescent cells.

What is inflammaging?

Aging is a natural process that none of us can avoid, but it’s fair to say that some of us experience it better than others and with fewer age-related complications. Why is that? Researchers point to inflammation. It’s one of the main factors that determines how we feel during the aging process. In fact, it’s considered one of the 12 pillars of aging, according to scientists [1]. Researchers say optimal aging is associated with a healthy inflammatory state, while elevated levels of inflammation are linked to accelerated aging and age-related conditions [2].

While no one can prevent aging, studies show that exercise, nutrition (including supplements), stress management, quality sleep, and other lifestyle factors can encourage a healthy inflammatory state as you age.

What causes inflammaging?

The causes of inflammaging are multifactorial. In addition to being an intrinsic process caused by aging, inflammaging can also be triggered by external environmental factors such as sun exposure, cigarette smoke, and pollution [3]. At the root of all of those factors is oxidative stress, which can trigger an inflammatory response from your cells. In addition to oxidative stress, inflammaging stems from genetic susceptibility, gut health, obesity, aging immune cells, and cellular senescence, those alive but non-replicating cells [3].

The connection between inflammaging and cellular senescence

As mentioned, senescent cells are alive, only they’re no longer replicating and dividing. The Hayflick limit, named for scientist Leonard Hayflick, suggests that a cell can replicate and divide about 50 times before becoming senescent. However, cellular stress can cause a cell to enter senescence before the Hayflick limit is reached.

Senescent cells essentially take up space—literally. Senescent cells are enlarged due to their continued growth without dividing. They continue to generate and eliminate waste. These cells secrete pro-inflammatory and proteolytic (those are enzymes that break down protein) factors, collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which can negatively influence nearby healthy cells and tissues. Think of a senescent cell like the one moldy strawberry in a pint of fresh strawberries. If you don’t remove it, the mold spreads to the rest of the healthy berries quickly.

Normally, senescent cells are cleared within days to weeks by our immune cells [4]. As we age, however, senescent cells accumulate—accumulating exponentially faster after 60 [5]—and impede immune function, creating a snowball effect that leads to even more senescent cells. As they build up and persist, senescent cells contribute to inflammaging. In fact, SASP is thought to be the leading cause of inflammation in age-related conditions [6].

Immunosenescence and inflammaging

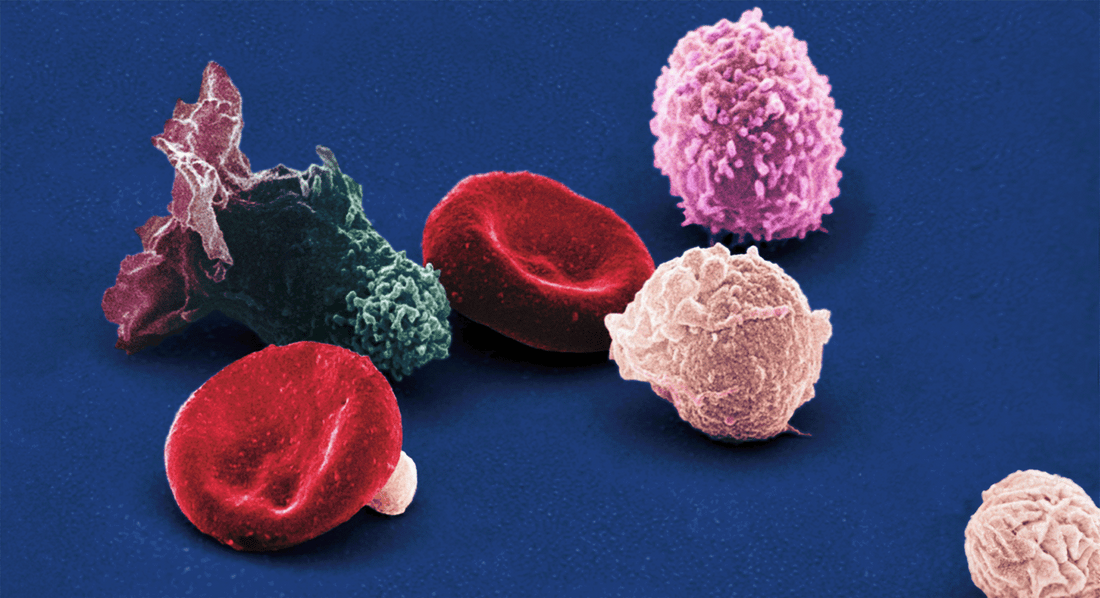

What’s immunosenescence? In short, it’s a term used to describe the aging of the immune system. Our immune system relies on specific immune cells to keep us healthy: B cells, which produce antibodies, T cells, which are cells that provide cell immunity, and NK or natural killer cells, which are white blood cells that destroy infected cells. During immunosenescence, the balance of immune cells shift toward pro-inflammatory cell types, including senescent immune cells that cease to replicate and secrete inflammatory molecules. All cell types in the body can become senescent (usually in response to cellular damage). With aging, the immune cells—which normally home in on, and clear these senescent cells—become senescent themselves, and the mechanism breaks down. Not only do senescent immune cells fail to clean up senescent cells, they secrete their own inflammatory molecules, adding to the inflammation surrounding healthy tissue.

How to support a healthy inflammatory state

Unfortunately, we can’t reverse the natural aging process, but we can harness innovations and interventions that help support a healthy inflammatory state as we age. The Inflammaging Complex in Elysium's immune supplement Format contains a patented blend of tamarind-turmeric extract, which has been clinically proven to reduce markers of inflammaging, including IL-6, CRP, and TNF -ɑ, in joint conditions and lessen knee discomfort after exercise [7-9]. The Complex also includes broccoli extract (a sulforaphane source), which further promotes a healthy inflammatory status [10]. Format also includes a Senolytic Complex, designed to be taken intermittently (two days a month). The Complex contains a senolytic formulation is based on leading institutional research in the field of cellular senescence and proven to clear senescent cells in two different human cell lines in laboratory studies.

References

1. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. Cell. 2023;186(2):243-278. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.001

2. Teissier T, Boulanger E, Cox LS. Cells. 2022;11(3):359. Published 2022 Jan 21. doi:10.3390/cells11030359

3. Pająk J, Nowicka D, Szepietowski JC. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):7784. Published 2023 Apr 24. doi:10.3390/ijms24097784

4. Chaib S, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1556-1568. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01923-y

5. Tuttle CSL, Waaijer MEC, Slee-Valentijn MS, Stijnen T, Westendorp R, Maier AB. Aging Cell. 2020;19(2):e13083. doi:10.1111/acel.13083

6. Sanada F, Taniyama Y, Muratsu J, et al. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:12. Published 2018 Feb 22. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2018.00012

7. Mortada EM. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e52041. Published 2024 Jan 10. doi:10.7759/cureus.52041

8. Prasad N, Vinay V, Srivastava A. Food Nutr Res. 2023;67:10.29219/fnr.v67.9268. Published 2023 Jun 20. doi:10.29219/fnr.v67.9268

9. Rao PS, Ramanjaneyulu YS, Prisk VR, Schurgers LJ. Int J Med Sci. 2019;16(6):845-853. Published 2019 Jun 2. doi:10.7150/ijms.32505

10. López-Chillón MT, Carazo-Díaz C, Prieto-Merino D, Zafrilla P, Moreno DA, Villaño D. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(2):745-752. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.03.006